HIV Testing

A Practical Reference for Integrating

HIV Testing Into Your Practice

One in 10 people in Philadelphia who have HIV don’t know they have it. Therefore, it’s crucial to offer HIV testing as part of routine lab work, especially if the individual is at a higher risk of HIV acquisition.

Provide Opt-Out HIV Testing

Opt-out HIV testing involves notifying patients that HIV testing will be conducted unless they decline, such as when blood testing is part of the planned workup.1

The CDC recommends that hospital emergency departments, primary care settings and other health care settings offer routine opt-out HIV screening as an evidence-based approach for HIV testing, regardless of reported risk behaviors.1

Everyone ages 13-64 years who comes in for care should automatically be offered an HIV test, without having to ask for one. These broad, age-based testing criteria increase the number of tests performed and also help to reduce the stigma associated with HIV.1

Under PA Act 59, a patient’s consent to an HIV test does not have to be in written form, but must be documented in the medical record by the clinician. Under this act, pre-test counseling is also not legally required (except for the requirements to explain the purpose, limitations, function, and result interpretation of the test).2

Offer the test as part of routine care. For example: “I’m ordering some blood tests today and I see you have not had an HIV test in the past year. I normally order an HIV test for all my patients and would like to add it to your blood tests today.”

Who Should Get Tested for HIV?

The United States Preventive Services Taskforce (USPSTF) offers the following Grade A recommendations for HIV screening:

- Adolescents and Adults aged 15 to 65 years,

- Younger adolescents and older adults who are increased risk of infection

- All pregnant persons, including those who present in labor or at delivery and status is unknown. 3

- HIV testing should be made available to everyone.1

People with the following risk factors should get tested at least once a year:

- Men who have sex with men (more frequent STI testing every 3–6 months may be considered based on individual risk factors) and

- Individuals who have had anal or vaginal sex with someone who has HIV.

- Individuals who have had more than one sex partner since their last HIV test.

- Individuals who have shared needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment (for example, cookers).

- Individuals who have exchanged sex, drugs, or other resources.

- Individuals who have been diagnosed with or treated for another STI.

- Individuals who have been diagnosed with or treated for hepatitis or tuberculosis.

- Individuals who have had sex with someone who has done anything listed above or with someone whose sexual history they don’t know.3

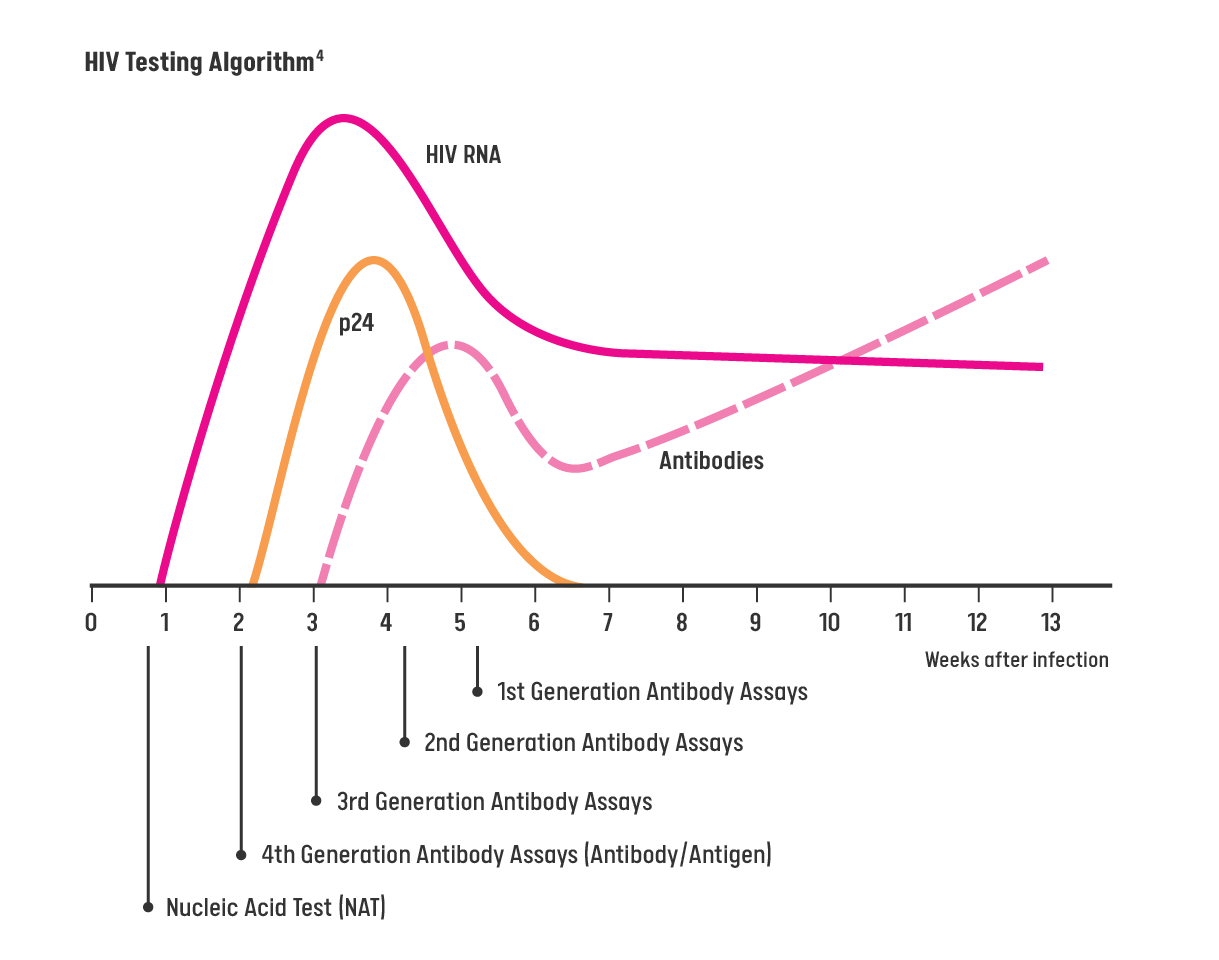

HIV Testing Algorithm

Patients should be assessed on the date/time of their last potential HIV exposure to ensure the lab test with the proper window period is being performed for an accurate, timely result.5

For patients who do NOT display signs or symptoms of acute HIV infection or do NOT report potential HIV exposures in the last 72 hours, a 4th generation (Ab/Ag) combination assay (or earlier generation assay) should be offered to screen for HIV.5

- For patients who are displaying signs or symptoms of HIV infection or report a recent exposure to HIV, a nucleic acid test (NAT) should be ordered to screen for acute HIV infection or prior infection. Patient should be assessed for PEP indication if potential HIV exposure occurred within 72 hours.5

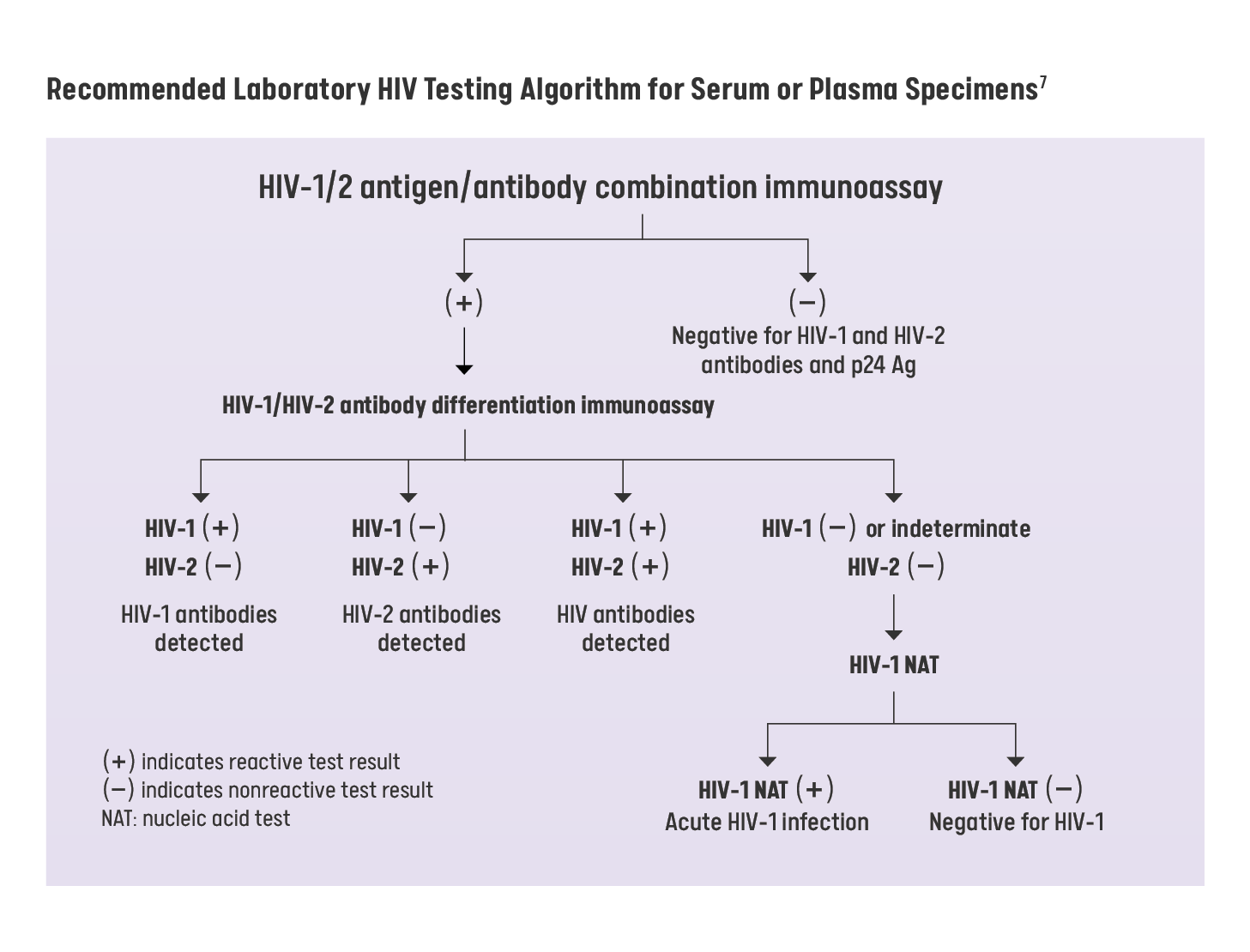

- All preliminary positive results from an HIV antibody screening or 4th generation Ag/Ab screening must be followed by a confirmatory test through NAT for HIV RNA).6

For More Information

Screening for HIV Infection US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2005/1201/p2287.pdfWho Should Get Tested? | HIV.gov

hiv.gov/hiv-basics/hiv-testing/learn-about-hiv-testing/who-should-get-testedScreening for HIV | Clinicians | CDC

cdc.gov/hivnexus/hcp/diagnosis-testing/index.html

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023a). How do I screen for HIV? | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/screening/how.html#opt-out

2. Rosica, J. (2011). Legislature changes Pennsylvania’s HIV-testing law. In AIDS Law Project of PA. AIDS Law Project of PA.

aidslawpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/gc_fall2011.pdf#:~:text=You%20must%20initiate%20an%20HIV%20test%20by

%20asking,the%20patient%E2%80%99s%20consent%20or%20refusal%20to%20the%20test.%2A

3. United States Preventive Services Task Force. (2019). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: Screening. In U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. United States Preventive Services Task Force.

uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-screening

4. Nikolopoulos, G. K., & Tsantes, A. G. (2022). Recent HIV infection: Diagnosis and public health implications. Diagnostics, 12(11), 2657.

doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12112657

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023b). Which HIV tests should I use? | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/screening/tests.html

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: Updated recommendations. In Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/23447

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Recommended Laboratory HIV Testing Algorithm for Serum of Plasma Specimens. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines_testing_recommendedlabtestingalgorithm.pdf